LATINOAMERICANO: About the Galleries

Organised into six sections, the exhibition explores Latin America’s complex geography, diverse identities, urban landscapes and artistic movements.

Instead of a chronological or geographical structure, it adopts a thematic approach, drawing connections between modern and contemporary art movements in Central and South America. These connections focus on thematic, formal, material, and conceptual elements to reveal both shared and distinct characteristics. This format helps visitors engage with the key ideas and debates that have shaped the region’s art.

Since the 16th-century, the colonial gaze has determined artistic and scientific representations of the Americas. Through their connections to avant-garde styles and perspectives, modern Latin American artists reinterpreted their own habitats from within, aiming to capture the exuberance and diversity of American geographies. Cuban-born artist Wifredo Lam, for example, incorporates imagery from sugarcane, palm leaves, and the light of the Caribbean in his work, emphasising anthropomorphic landscapes. Through this approach, Lam merges plant, animal, and human qualities, referencing and reconciling his Afro-Cuban traditions, which are both imaginative and mystical.

In exploring these interconnections, some artists also address the relationship between human and non-human species, delving into themes of nature, community, spirituality, and the vulnerability of the natural environment. Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe particularly highlights this communal ecological belief system in which everything is interconnected as a living organism. In this regard, both Hakihiiwe and Mogaje Guihu, also known as Abel Rodríguez, create affective records of their environments combining botanical knowledge with their ancestral practices.

Other contemporary artists choose to emphasise environmental degradation in their works. Starting from the mid-1960s, Nicolás García Uriburu’s colourised interventions on water and the resulting photographs drew attention to water pollution worldwide. Similarly, Mónica Girón focuses on the transformations of the environment, exploring the fluid relationship between the planet and the self.

Vida-Americana

In the 20th-century, artists focused on finding authentic means of representing modern Latin American identity. David Alfaro Siqueiros’ influential magazine Vida-Americana (1921) set out a series of manifestos inspiring Latin American artists and intellectuals to engage with rich vernacular elements drawn from the visual and material traditions of American cultures. In this way, local music and dances, such as sandunga, tango, and candombe, are shown in the works of Diego Rivera, Emilio Pettoruti, and Pedro Figari. Similarly, Antonio Berni and Candido Portinari depict typical gatherings, such as celebrations and marketplaces, that explore community life.

Portraiture not only served as a popular means of self-expression but also engaged with similar ideas. Frida Kahlo, for instance, represents herself wearing a huipil an embroidered cotton blouse with her braided hair intertwined with thick green yarn in the typical fashion of native women from Central and South Mexico. Having fled Europe due to ongoing wars, Alice Rahon and Remedios Varo also incorporate diverse cultural elements in their art from their newly found homes in Mexico.

In contrast to modern artists, contemporary artists such as Belkis Ayón and Rosana Paulino take a critical approach to modernist representations of Afro-Latino identities. In doing so, they engage with the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the African diaspora in the Americas. Paulino, for instance, utilises archival photographs, textiles, and poetry to dismantle ideas perpetuated by colonial and scientific racism, aiming to re-examine Afro-Brazilian identity.

Cidade City Cité

Transformations in urban living impacted the way artists reconceptualised their own practices. Cities became a key topic for avant-garde artists, serving as avenues for the circulation of new ideas and creative exchange. Rafael Barradas and Joaquín Torres García, who were based in Europe for many years, explored the concepts of juxtaposition and fragmentation in their works. Meanwhile, the photography of Horacio Coppola and Geraldo de Barros sought to encapsulate the developments of the city through different framing and experimental methods.

Cities are also unique spaces for artists to imagine utopian ways of living. On the one hand, Lidy Prati, Hélio Oiticica, and Gonzalo Fonseca employed geometric abstraction to imagine a world where art can influence and define every aspect of urban life. On the other hand, surrealists Juan O’Gorman and Alejandro Xul Solar modelled their vision of the city by connecting diverse visual traditions ranging from Roman columns to stereoscopic three-dimensional views.

Poetry also took part in avant-garde representations of the city, particularly in the works of concrete poets. Taking on a more visual arts and design approach, their work focused on the structural, phonetic, and typographic elements of poetry to convey meaning. For example, in Cidade City Cité (1962), Brazilian concrete poet Augusto de Campos discusses what defines a city and incorporates words that end with the suffix “cidade” (city in Portuguese) to create a poem composed of a single line of interconnected words.

The Independence of Art — For the Revolution

The 20th-century witnessed radical social, political, and cultural transformations across the world. Workers' demonstrations, student revolts, military confrontations, and other leftist movements were catalysts for these changes. Artists reacted to these events with protest imagery playing a central role. Leon Trotsky, who was exiled in Mexico at the time, along with Diego Rivera and Andre Breton, underlined the importance of art in these newly formed societies in their 1938 Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art.

The Mexican Revolution in 1910 transformed not only the social conditions of its people but also its visual culture. Since the 1920s, artists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera put into practice a new Mexican modernist language by painting large murals. These murals, mainly located in government buildings, focused on revolutionary struggles and ancient indigenous cultures. Mexican muralism inspired other social movements in Latin America, such as Andean Indigenism, represented by artists like Alejandro Mario Yllanes and Jesús Ruiz Durand.

In the 1960s and 1970s, longstanding dictatorships in South America were met with collective protests resisting the systematic violence of these regimes. During this period, anti-capitalist sentiments and the structural exclusions of different communities fuelled many artistic practices. For instance, Cildo Meireles marked Coca-Cola bottles with various statements before returning them to the marketplace to spread anti-establishment messages. Mail art was another way to bypass severe governmental control. Chilean visual artist Eugenio Dittborn used the post to communicate his anti-dictatorial beliefs and the widespread disappearances far beyond Chile’s borders.

A Poem in Space

Created by Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña in 2018,Quipu desaparecido is a multisensory installation.

Image: Quipu desaparecido (Disappeared Quipu) (2018) by Cecilia Vicuña (1948, Santiago, Chile), Wool and video projection with sound, Eduardo F. Costantini Collection

Photo: Wadha Al-Mesalam, courtesy of Qatar Museums ©2025

The Andean civilisation developed quipus—knotted strings comprised of coloured, spun and plied wool or llama hair as a method of recording information. This practice documented various aspects of societal organisation across the ancient Incan Empire, including tax obligations, calendrical information, and military planning. Quipus were also used to record poems and historical narratives. Inspired by these threads, Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña created the monumental multisensory installation Quipu desaparecido (Disappeared Quipu) in 2018. Through four-channel video projections, the piece acts as an homage to ancient people and their ways of life decimated by Spanish colonisation. Vicuña has devoted a significant part of her artistic practice studying, interpreting, and reactivating the quipus. For her, the quipu is “a poem in space, a way to remember, involving the body and the cosmos at once.”

Between Lines and Light

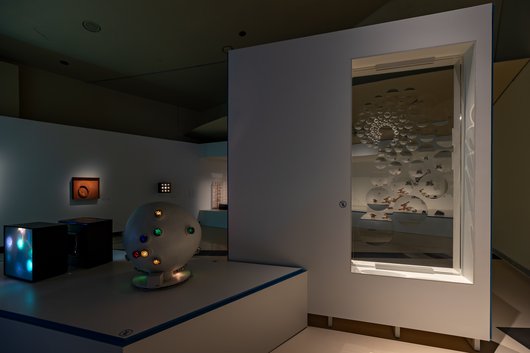

In the second half of the 20th-century, driven by changes in urban and societal structures, Latin American art witnessed a significant transformation in its visual language. Artists began to challenge traditional visual arts disciplines, focusing on their construction and materiality and radically changing their conventional display methods. Notable figures such as Martín Blaszko, Juan Melé, and Diyi Laañ abandoned the established rectangular structure of paintings for cutout and irregular frames and compositions. Similarly, Gego (Gertrudis Goldschmidt) moved away from placing her works on pedestals to suspending them from the ceiling. These innovative pieces emphasise the interactions between lines, space, light, and shadows.

The transformation of the art object aimed to extend beyond mere modifications in display and style. In the 1960s, Lygia Clark developed her Bichos series, also known as Critters, which consisted of hinged aluminium sheets. These artworks encourage viewer interaction by allowing movement, resulting in the creation of various shapes and positions. Kinetic art also emphasises this dynamic engagement.

Creations by Gregorio Vardanega, Julio Le Parc, and Martha Boto are activated through light and motors, generating physical movements. While in Alejandro Otero’s piece Coloritmo en movimiento 6 (Colorhythm in Movement 6) (1957), the perceptual illusions are caused by the superimposition and overlapping of linear and geometric patterns. These works expand viewer interaction into a participatory experience.