Clothing and Fashion

Apparel is shaped not just by climate and the availability of materials, but also social values, aesthetics and transnational trends. Whether store-bought or home-made, clothing is part of the way we all express and re-imagine our identities.

The symbols and motifs women incorporate in the finely crafted textiles and beautiful embroidered clothes they make are part of their community's heritage. At the same time these objects tell a story about the sense of self of those who wear them and the appreciation of beauty, propriety and grace of those who make them.

Like other cultural expressions, dress can change in form and meaning. Designers today in Qatar are creating abayas using new prints, fabrics and shades of colour to reinterpret tradition.

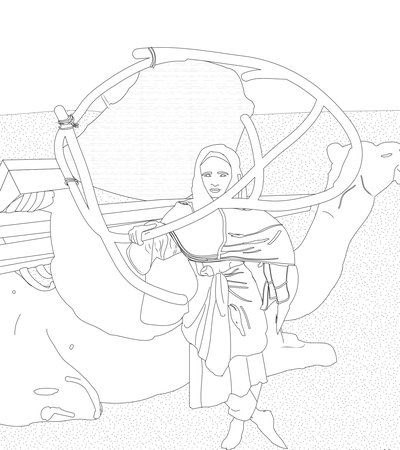

While traditional garments can be influenced by fashion trends and changes in popular taste, they also serve as inspiration for fashion and the arts. The world, and Hollywood in particular, has long been fascinated with Mongolian deels, hats and boots, while contemporary fashion has drawn on motifs and designs from Imuhar indigo clothing and silver jewellery.

Celebrations of Community and Heritage

Gatherings such as festivals, religious feasts and sporting events are an eagerly anticipated opportunity for people to spend time with family and friends, reconnect with distant relatives and celebrate their heritage and faith.

Eid Al-Fitr and Eid Al-Adha celebrations in Qatar and across the Muslim world, and more recent music festivals, such as the Festival de l'Air in Niger, are also occasions for men and women to dress in their finest clothes and jewellery.

In Mongolia, the centuries-old Naadam summer games were given nationalist meanings after the Soviet-backed 1921 revolution, while from the 1930s, military parades were added. Today the festival brings together tens of thousands of people to watch competitions of archery, wrestling, horseracing and knuckle-bone shooting.

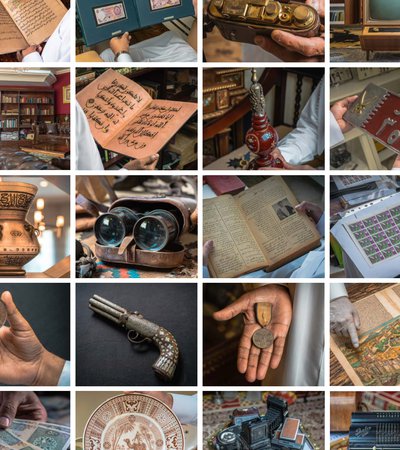

Negotiating the Unknown: Amulets and Divination

Human beings everywhere negotiate their relationship with the unknown. We can see some of the ways they do so through their religious practices and objects.

In Qatar, women and young girls in the pastoral communities used to wear a tableh, a pendant in which verses from the Qu'ran were placed as a protection.

Many Imuhar nomads used to wear one or more of the flat leather pouches called teraut, into which are sewn religious texts to protect them from illness or bad luck.

Mongolians also wear amulets or keep them at home as protection and use various forms of divination, such as 'readings' of the pattern of cracks and colours made by putting a sheep scapula (shoulder blade) into the fire to get answers to questions about livestock, health and social relations.

The Virtues of Hospitality

In all three regions, being a good host and a good guest is expected and respected.

In the central Sahara, guests are welcomed with a bowl of fresh milk, followed by tea. The sugar for the tea was, in the past, chipped from a sugarloaf with a small, often richly decorated hammer, an unusual and rare single-purpose tool that shows how important offering tea to guests was among these nomads.

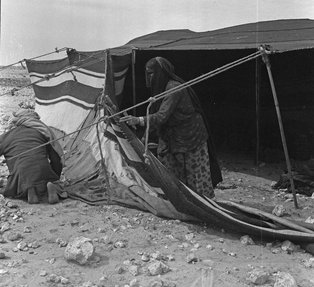

In Qatar, guests are received in the majlis, or the guest section of the tent, where they are served coffee with dates, provided meals and offered sanctuary if needed.

In the Mongolian countryside, visiting occurs on many occasions. Passing travelers can expect milk tea and cheese curd or fried breads from their hosts.